From other coronavirus outbreaks (SARS and MERS), we know that if an infected patient enters a busy hospital environment undetected, the virus can be transmitted to other patients, and in no time a hospital-wide outbreak can result.

The key to keeping hospitals safe is the early identification of cases before entry to the hospital. At the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak, in the UK patients were assessed based on epidemiological risk factors. Current risk assessments are based on the identification of patients presenting with new onset of respiratory symptoms, or clinical or radiological evidence of a chest infection. These risk assessments need to be performed either before patients come onto site, or before they interface with the hospital. If attending outpatients, for example, patients should be asked if they have any respiratory symptoms as per the case definition. If they confirm symptoms, they should be placed in a separate room or asked to wait two metres away from everyone else. External isolation pods were often used in the early phases, or patients were assessed in their own cars.

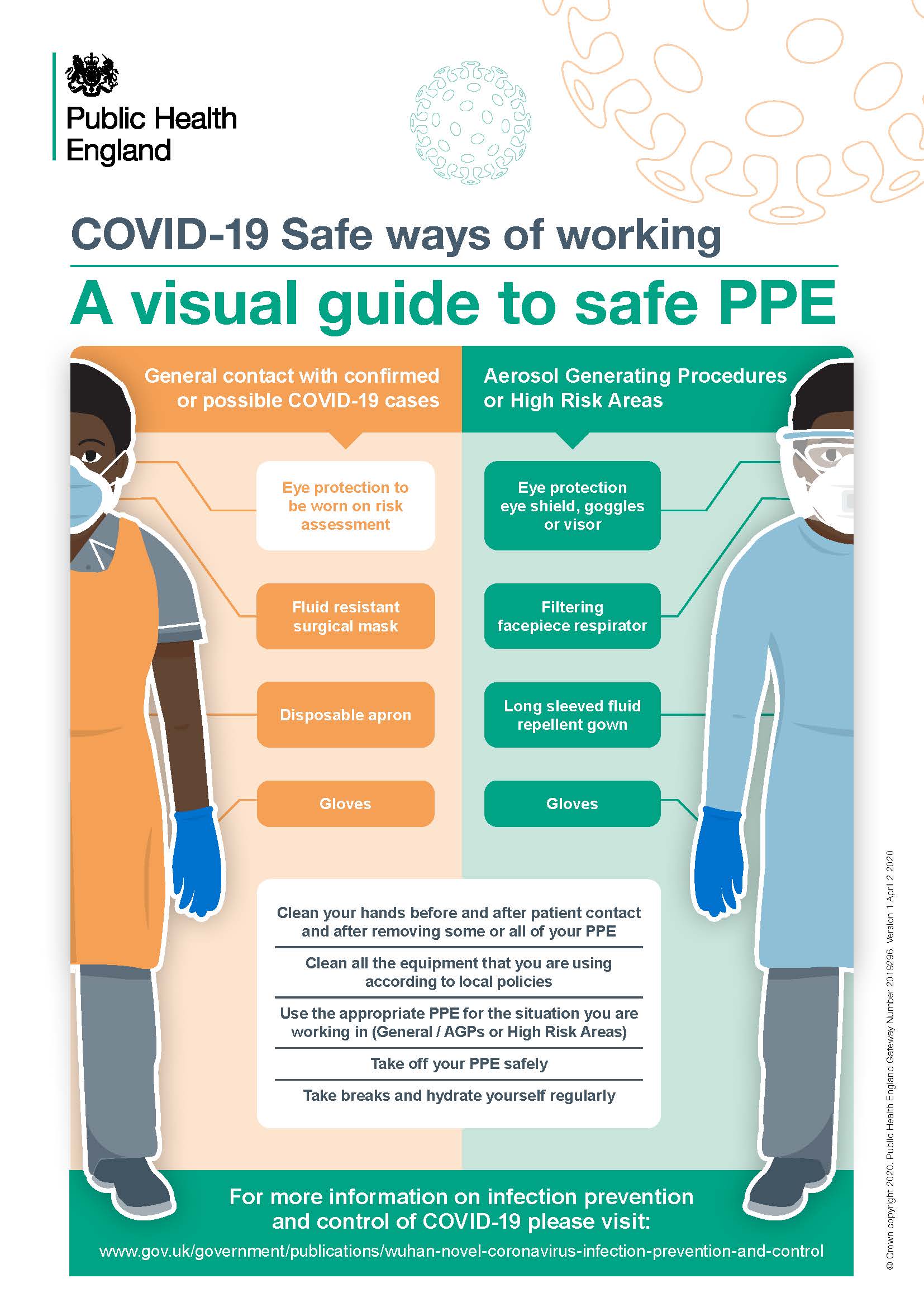

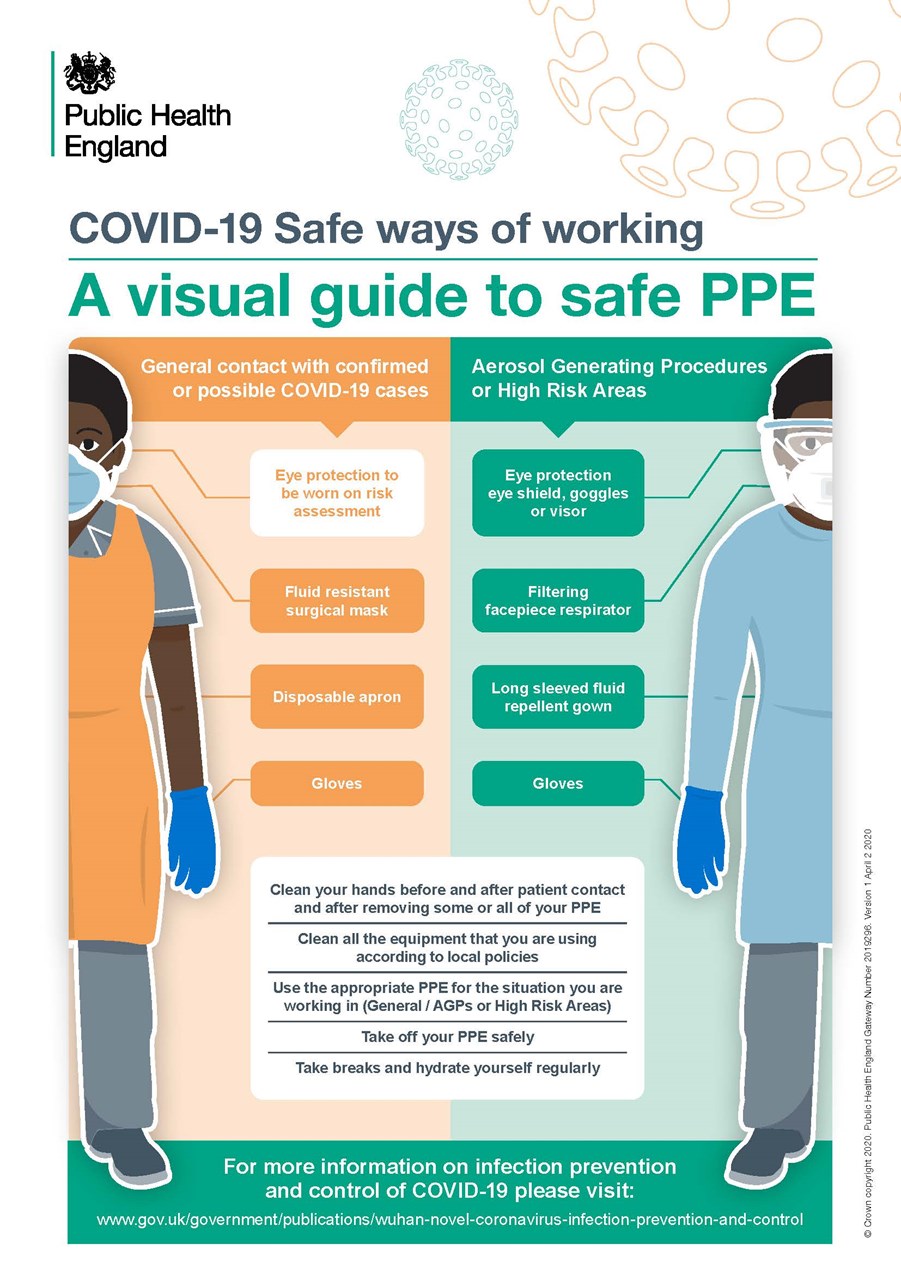

Once identified as a possible case, healthcare workers (HCWs) must isolate patients to minimise dispersal of the virus, and wear the correct personal protective equipment (PPE). Patients should be encouraged to use tissues if they cough or sneeze, or alternatively be provided with a surgical mask to wear if it is safe to do so.

The virus needs to reach the nose, mouth or eyes in order to enter the respiratory tract and cause COVID-19. Like other respiratory viruses, SARS-CoV-2 has developed successful strategies to reach these areas. When a patient with a respiratory tract infection coughs or sneezes (sneezing is thought to be a less common symptom of COVID-19), the virus is expelled from the respiratory tract. There are then various routes of transmission:

Coughing and sneezing lead to the expulsion of droplets containing the virus. These droplets are large and do not remain suspended the air, but fall onto surfaces up to two metres from the patient. If you are outside a two-metre zone when the patient coughs or sneezes the risk from droplet spread is very much reduced.

Protection from droplet spread is provided by a barrier such as a fluid repellent surgical facemask with a visor. The World Health Organization have maintained throughout that a surgical facemask with visor is effective protection when looking after a known coronavirus patient unless aerosol generating procedures (AGPs) are performed.

The correct use of a surgical facemask is demonstrated in this video:

Safe use of surgical face masks (3:31 duration)

Fluid repellent surgical face masks, together with eye protection, can be an effective barrier to transmission of SARS-CoV-2 by droplet spread: the virus is captured by the mask and prevented from accessing the eyes, nose and mouth. However, viable virus may be present on the surface of the mask and eye protection, and can be a source of cross-infection if the mask and eye protection are not used safely. In particular areas, it is recommended staff do not change their surgical mask and eye protection between patients, whilst working within designated boundaries for that session. A session ends when staff leave the designated care setting or exposure environment. This helps preserve PPE stocks – but more importantly, reducing the number of times the PPE is removed lessens the risk of acquiring infection through improper removal. It is of paramount importance that the mask and eye protection (after donning) are only touched at the time of removal, using the correct doffing technique.

By touching facemasks and eye protection after donning, the virus can be transferred to the wearer, to another person or to highly-touched surfaces, which are then touched by other staff.

After donning, you should:

The listed practices are not safe, and put you, your work colleagues and your household at risk of infection.

Direct contact occurs when you directly touch patient secretions or touch the patient. The patient’s hands in particular are likely to be heavily contaminated. Protection to HCWs is offered by using PPE, performing regular hand washing and not touching the nose, mouth or eyes.

Important: Indirect contact occurs through touching intermediate surfaces onto which the virus has been transferred, such as a door plate, a handle or other highly-touched surfaces. The virus may survive for up to 5 days in the environment: protection is afforded by frequent cleaning of surfaces, regular hand decontamination and avoiding touching the eyes, nose and mouth.

Airborne spread may occur when medical teams perform AGPs. Surgical masks will not protect the wearer as air and virus may be drawn in behind the mask when such procedures are performed. For AGPs where spread is a risk a FFP3 mask is required.

FFP3 masks work by filtering the air. This necessitates there being a good seal between the mask and the wearer’s face to force the air to pass through the mask filter. Fit testing is essential, and an FFP3 should not be worn if you have not been fit tested, or you have failed fit testing or have facial hair which would interfere with obtaining a proper seal. In these instances, a powered positive pressure respirator may be used.

AGPs should ideally be performed in a negative pressure room or side room. Only essential staff should be in the room and the door should be kept shut. All surfaces should be cleaned 20 minutes after the end of the procedure.

The required type of PPE and how to don and doff correctly is summarised below. PHE guidance should always be followed.

When donning and doffing PPE, a buddy is an important requirement to help you check through the processes. A buddy is your protection, checking that you follow the procedures safely and reminding you to decontaminate your hands at each stage.

Direct and indirect contact spread is an important route of transmission and is often underestimated. Observation of individuals shows hands frequently come into contact with mucous membranes, and can introduce the virus where it will replicate in the respiratory tract. Hand hygiene should not just be performed after direct contact with a CODIV-19 patient or their secretions, but when a HCW enters the environment – as detailed in the WHO My Five Moments of Hand Hygiene. The virus may be widely distributed around the patient, so once a zone is entered any contact is likely to encounter the virus.

Door handles, lobby areas and highly-touched surfaces need to be frequently disinfected to inactivate the virus. Hand hygiene techniques must be performed correctly, and hand wash stations must also be used correctly. Alcohol hand rub must be applied correctly to cover all surfaces of your hands: otherwise, areas such as fingertips (which are important contact points) may be left out.

The use of a hand to move elbow-operated outlets can transfer pathogens onto tap handles.

Even if a good hand washing technique is performed, using the hand to turn off the outlet results in instant recontamination. HCWs should use elbows to operate outlets where possible. Alternatively, after washing, the tap may be left running, hands dried with a paper towel and then a towel used to operate the outlet, thereby avoiding direct contact.

The Healthcare Infection Society is grateful to Dr Mike Weinbren and the team at Sherwood Forest Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust for permission to transcribe and share the following videos:

COVID-19 – an overview (11:39 duration)

Safe use of surgical face masks (3:31 duration)

Dr Weinbren’s blog from 2019 Hand wash stations – designed for decontamination or re-contamination of hands? looks at how effectively healthcare staff use handwashing stations.